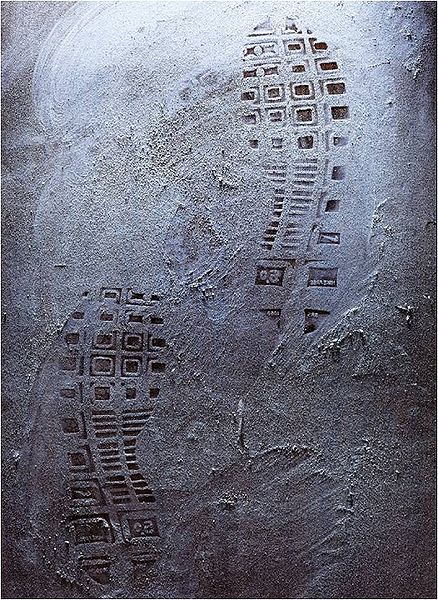

(Image licensed by Colleen Collins)

Welcome back to Surveillance 101, a series of classes my husband and I taught in 2011 to a mystery writers' group. I've updated course information for this blog, and added new material as well.

COPYRIGHTS

All content is copyrighted, so please do not copy, distribute, and so forth. Within the captions of photos, I note if it is copyrighted, licensed or within the public domain. The only photos you are free to copy/use are those marked as public domain.

LINKS TO CLASSES 1 - 4

Surveillance 101: Staying Legal, Dressing the Part, Prepping the Vehicle

Surveillance 101, Part 2: The Importance of Pre-Surveillance and Knowing if a Subject Has a Lawyer

Surveillance 101, Part 3: Picking a Spot, Difference Between Mobile vs. Stationary

Surveillance 101, Part 4: Tips and Tricks About Mobile Surveillances

In this class, we cover surveillance logs, rural surveillances, and watching out for tedium.

Keeping a Surveillance Log

PIs take surveillance notes in a variety of ways, from handwriting notes to leaving voice messages

We like to keep a surveillance notebook handy in our vehicle. It’s easier in the long run, we’ve found, to jot down pertinent notes rather than dictate information into a recorder because later, as we’re writing the report, playing and replaying a recording can become time-consuming versus simply reviewing handwritten notes. Yes, even in this electronic age some old-fashioned means work best.

Some PIs use sheets with tables, some make notes in their smartphones, or once in the dark when Shaun couldn’t see his hand in front of his face, much less what he was scribbling on a notepad, he called home and left short surveillance-status messages on our office voice messaging (which he later listened to as he wrote up the report). Whatever medium a PI uses, here’s a sampling of data she'll document during a surveillance:

- Time, weather, location at start of surveillance

- Time of any action by the subject (and what he/she might be wearing, their behavior, etc.)

- Record of subject’s actions

- Addresses where subject goes

- Description of people meeting with the subject (includes vehicles & license plates).

It's critical to plan ahead for a rural surveillance (image is in the public domain)

Rural Surveillance

Below are some tips if your fictional PI conducts a surveillance in the country:

Know the area

Here in Colorado, we have some big stretches of country outside “the big cities.” When we’re going into a rural area, we’ll check online maps (for example, MapQuest, Google Earth) -- have your fictional PI do the same.

On the other hand, if you’re looking for more conflict in your story, have him circling around and attracting unwanted attention in that small town!

Use an appropriate vehicle

Maybe your fictional PI scoots around town in a lime-green VW, but that dog won’t hunt in the country. In a small town, everybody knows everybody else, including what car they drive. A PI will drive a vehicle that blends in, is nondescript, and can handle the terrain. This ties in with information in the previous class about surveillance vehicles (a pick-up truck makes more sense in the country, for example). Another tip: A sparkling, shiny-clean vehicle can also stand out -- vehicles get dusty and dirty driving around the country.

Why is the PI parked there?

When conducting a rural surveillance, a PI doesn't want to stand out as a city slicker trying to look country (image licensed by Colleen Collins)

A PI can be parked on a country public road and document whatever he sees “in plain view” — but he’d better have a good reason for being there if someone asks. Most PIs keep props ready, such as binoculars and a bird guide (pretending she’s a bird watcher), car-repair tools (pretending he’s fixing his car), and so on.

A side note here about bird watching. A writer friend, whose husband is an FBI agent, laughed at the idea of a PI pretending to be a birdwatcher. "My husband says that cover is ridiculously cliche, and clues the locals in that you're really a snoop." Which presents some fun ideas for a story:

- The PI, who never heard bird watching is an obvious cover, puts great effort into faking watching birds (wearing the clothes, reading books about birds, invests in special binoculars) and gets instantly burned (meaning "outed" as really being a private detective).

- The PI blows off her PI-buddy's warning about never using the old-as-the-hills birdwatching cover, and pulls off a masterful surveillance using the guise, irking her pal no end.

- A PI goes out of his way to create a unique cover only to get burned by a local who says his guise was pretty obvious...shoulda tried birdwatching as that would've fooled people.

Look the part

Just as a PI wears clothes appropriate to a city location, he’ll wear clothes that blend in to that part of the country/season. When we did a rural surveillance in Colorado, we wore jeans, t-shirts, boots (it was winter), jackets.

Choose useful equipment

It’s always iffy if a cell phone will have adequate transmission in remote areas (which can add a twist to your story), but other equipment can be selected for rural surveillance (cameras with increased optical zoom, video equipment that is functional, portable, and low profile).

Surveillance, the Glamorous Life (Not)

We’ve discussed a PI’s clothing, supplies, logistics, vehicles, and techniques, but there’s another aspect to surveillance: the tedium factor. As one PI put it, surveillance is “95 percent boredom and 5 percent panic and fear.” During those long stretches where nothing is happening (the 95 percent boredom part), some real-life PIs get into trouble thinking they can wile away the time by watching DVDs, reading books, or other distracting entertainment. All it takes is a few seconds for a subject to appear…and disappear. A PI focused on anything other than the subject can easily, within those few seconds, lose him/her.

On the other hand, you can make this a funny bit in your story that every time your fictional PI decides it’s okay to pick up that novel while on surveillance, he misses the subject again!

Next class, we'll cover PIs' health concerns during surveillances, and the good, bad and illegal of GPS tracking.

Coming Soon: How Do Private Eyes Do That? Second Edition.